In today’s increasingly global education landscape, standardized tests play a central role in determining access to higher education. In the United States, the SAT is a vital part of the college admissions process and is also accepted by universities worldwide. In Nigeria, the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME), organized by the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB), serves a similar purpose – determining who gains admission into tertiary institutions.

Yet, one major difference separates these two exams: how often they are offered.

The SAT is offered seven times a year; in March, May, June, August, October, November, and December. This frequency is not accidental; it is a deliberate effort by the College Board to meet the diverse needs of students.

Students apply to colleges at different times, including early decision, regular decision, or rolling admissions. Multiple SAT dates ensure that no matter when a student is ready or when their application is due, they have access to a test date that works for them. It also allows room for retakes, which many students take advantage of to improve their scores or benefit from “superscoring,” where colleges combine the best section scores from different test dates.

The flexible SAT schedule also reflects differences in academic readiness. Not every student is equally prepared at the same point in the year. Some may want to take the test after completing specific math courses or during summer when they have more time to prepare. Additionally, the SAT serves a broad range of test-takers, from high school students and gap-year applicants to international students and adult learners, each with different timelines and commitments.

By offering multiple test dates, the SAT gives students greater control over their application journey. It recognizes that education is not linear and provides second chances, flexibility, and fairness.

JAMB/UTME: Centralized System with Limited Opportunity:

In contrast, Nigeria’s UTME is offered only once a year, typically between March and April. This single annual sitting is shaped by Nigeria’s centralized admission system, where all public and many private institutions admit new students at the same time, usually in the fall. As a result, a single testing window is seen as sufficient from an administrative standpoint.

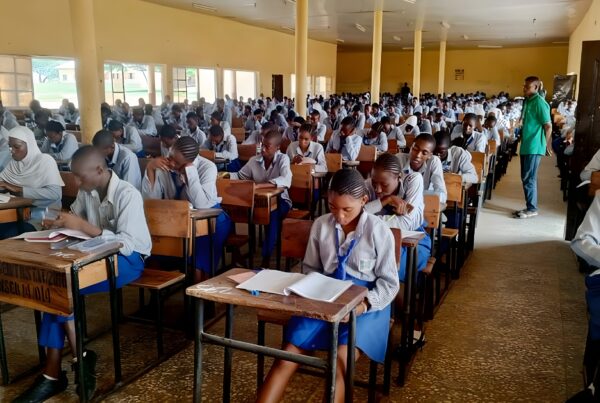

There are also logistical constraints. Conducting the UTME involves over 1.5 million candidates, hundreds of CBT centers, and extensive coordination across the country. Running the exam multiple times a year would be costly and challenging, particularly given infrastructural limitations.

Nigeria’s tertiary institutions also operate on a rigid academic calendar, with only one admission cycle per year. Without a system for rolling admissions or mid-year entry, offering UTME more than once could lead to confusion and misalignment with university processes.

The Hidden Costs of Once-a-Year Testing:

While offering UTME once a year may be practical for JAMB, it creates significant disadvantages for students.

First, the high-stakes nature of the exam causes enormous stress. A student who falls ill on exam day, experiences a technical failure, or underperforms due to nerves must wait an entire year for another chance. This is unlike the SAT, where a poor result in March can be addressed by retaking the exam in May or June.

Secondly, the system does not accommodate unforeseen circumstances. Power outages, internet glitches, or administrative errors at CBT centers can cost students their only shot for the year, often through no fault of their own.

This model also contributes to a large population of “JAMB repeaters” (students who spend two or more years retaking the exam in hopes of securing admission). It causes emotional strain, delays career progress, and places unnecessary financial burdens on families.

Furthermore, the once-a-year system limits innovation in higher education. It prevents the implementation of rolling admissions, mid-year entries, and more flexible academic planning. It essentially holds back Nigeria’s progress toward a more modern, inclusive, and responsive education system.

What Can Be Learned?:

The comparison between the SAT and UTME reveals a broader truth: frequency matters. Multiple test dates create a more equitable, accessible, and student-friendly process. They allow for second chances, reduce pressure, and give students the opportunity to plan their academic journey with confidence.

While JAMB may not be able to immediately shift to a year-round testing model, incremental reforms, such as a second annual sitting or more flexible exam windows, could make a meaningful difference. As Nigeria continues to invest in digital infrastructure and education reform, revisiting the exam schedule should be part of the conversation.

Access to higher education should not be determined on a single day. The SAT’s multiple test dates demonstrate the value of flexibility and student-centered policies. For Nigeria’s JAMB/UTME system, adopting similar principles, within its context and capacity, could unlock new possibilities for millions of students seeking a better future.